Paul Kingsnorth is a writer living in rural Ireland. In 2009, he created and launched Dark Mountain Project, a writers’ and artists’ movement designed to question the stories our culture is telling itself in a time of ecological and social unraveling. Paul has won various prizes for his poetry, including the 2012 Wenlock Prize. His first novel, The Wake, was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize and won the Gordon Burn Prize and the Bookseller Book of the Year Award. Paul’s second novel, Beast, was shortlisted for the Encore Award for the best second novel. The third, and final, installment in this trilogy, Alexandria, is forthcoming. Paul published his first collection of essays, Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist, in 2017, and his most recent nonfiction book, Savage Gods, was released in 2019.

Studio Airport, founded by Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters, is an interdisciplinary design studio that ventures out into the cultural ether to forage for anomalies, creating work that spans art, culture, science, and ecology. In addition to Emergence Magazine, their creative partners include the Design Museum, See All This Art Magazine, Slowness, Normal Phenomena of Life, and Sapiens Magazine. They serve as master tutors at the Design Academy Eindhoven and were recognized as European Agency of the Year 2024 by the EDA.

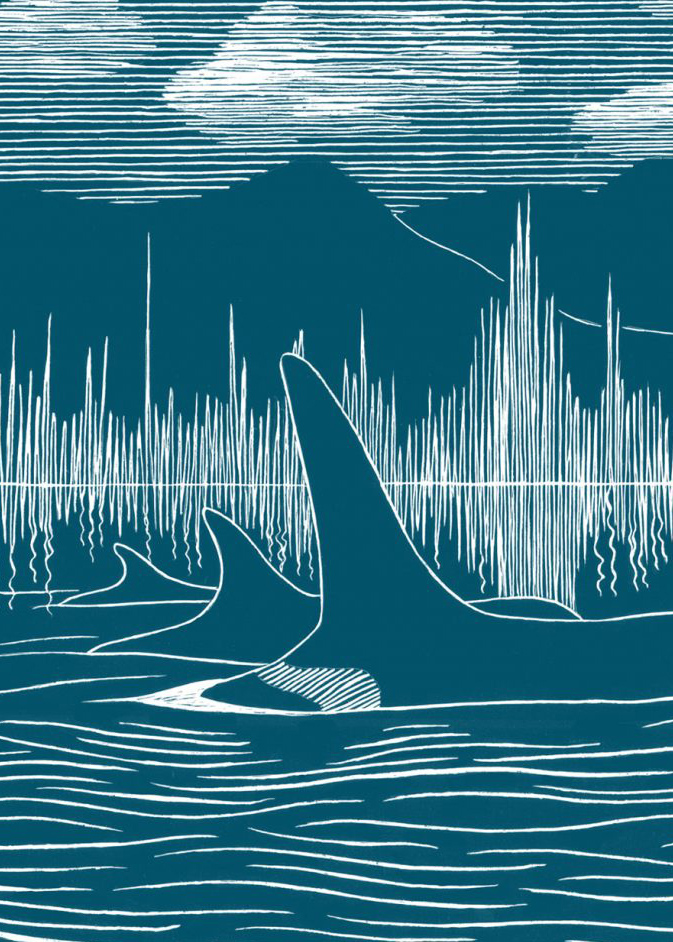

In examining the consequences of written language, writer Paul Kingsnorth comes to terms with his own profession, arguing that the written word is, in fact, a tool of ecocide.

What defines a human? What is the essence of what we are?

Perhaps it is the ability, and the desire, to ask questions like that.

At some level, the “culture” inhabited by people like us—people who read, who write, who think, who worry, who accept these questions as valid—is a culture of separation; an orthodoxy of subject and object. Something separates “us” from “them,” where “us” is Homo sapiens, a species of upright hominid, and “them” is every other living being that inhabits this living Earth. What is the source of this separation? Is it God? Were we created to be different, to be masters, or stewards? Did we “evolve” our differences? Why do we think we are different, anyway? Is it because we are the only species that writes essays?

These are circular questions. Like Earth and its seasons, they never stop turning.

What is the dividing line between us and them? Is there one at all? In one sense, no. We are a primate species, virtually genetically identical to our closest hominid relative, the chimpanzee. We share many of their behavioral characteristics, and have much in common with other mammals, with all life. We are born, we die, we compete, we cooperate, we reproduce, and the patterns in which we do all of these things are clearly predictable from our evolutionary history.

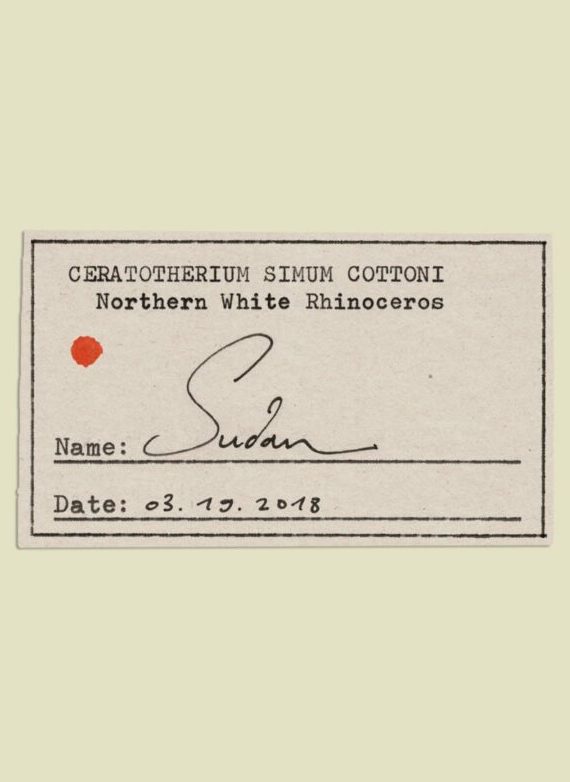

Yet we are, at the same time, kidding ourselves with this sort of talk. We are not just another species of ape, and even those, like myself, who would like to think so—who would like to believe that some return might be possible—know that it is not. We are apart. The very fact of that apartness is what has, amongst other things, reduced the numbers of other apes to critical levels and changed the biosphere of the planet itself. Something makes humans different: makes us so all-dominating, so all-consuming, that in the eyeblink of time in which our species has been around—a mere 300,000 years, out of the 4.6 billion that Earth has existed—we have engineered a planetary shift bigger than anything seen in eons, we have done so knowingly, and we still, despite all we know, refuse to stop.

What is it that gives us this power? Fire? Tools? Weapons? Or the thing that is each of these, and all of them at once: language?

Language is both our most effective tool and our most powerful weapon. If you want to see how powerful this weapon is, look around. A simple conversation can be a skirmish: setting out positions, pushing back and forth, testing the ground. Most obviously, the way we use language when we disagree is often militarized; and when the issues under discussion are existential, the linguistic warfare can break out into the open.

In his essay “Politics and the English Language,” written in 1946, George Orwell explains how language is “an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.” Writing soon after the defeat of fascism, but with communism now aggressively on the ascendant and clashing with the liberal-capitalist West, Orwell had plenty of opportunities to study how language was used dishonestly to fight political and cultural wars, and how the winners would use the opportunity to rewrite the speech patterns—and thus the ways of seeing—of the losers. Since the words we use reflect our worldview, controlling language helps control the picture that we see of the world.

Nothing much changes. In the riven political and cultural atmosphere of today’s Anglophone West, we don’t have to look far to see the use of language tied up in cultural and political battles. Most obviously, it is seen in the daily struggle to use words to pin down an opponent. Define the terms that others must use, and you already have the upper hand. If you want to caricature the arguments of those who speak out against the current liberal-capitalist consensus, for example, you call them “populists.” What does this mean? Nobody agrees. But it is an effective way of diminishing the worldview of your opponents, or simply miring them in argument or denial.

Similarly, and usually from another perspective, accusing your opponents of being “politically correct”—another label that few people ever consciously apply to themselves—has a similar effect. If you’re feeling more aggressive—or simply losing the argument—you might get out the big guns. Your opponent may become a “snowflake” or a “social justice warrior,” a “hater” or a “fascist.” By this point, war has broken out into the open. Now, people are not arguing about issues—about ideas, proposals, feelings, approaches—they are trading in which insult is most likely to stick. In the age of easy-click social media outrage, these kinds of linguistic skirmishes have a depressing, routine familiarity.

Dishonest use of language is one way of using words as a weapon. Another is designing, and enforcing, linguistic—and thus, cultural—orthodoxy. This kind of language policing was an open feature of state communism, in which the incorrect use of, or resistance to, officially-approved terminologies could lead to a show trial and even death—a situation memorialized by Orwell through his invention of “Newspeak” for his novel 1984.

But while language—and thus, thought—policing is most obvious in totalitarian regimes, some form of it goes on in every culture. Language policing is a timeless method by which a cultural or political elite establishes and holds on to power. The ideology of that elite may vary—communist or fascist, progressive or conservative—but their enthusiasm for telling the masses how to use language is never dimmed.

In Britain a century ago, for example, there were clear linguistic boundaries which writers could not cross if they did not want to see their books banned or their reputations damaged, and the markers for what was “decent” public language were clear and enforced. What today would be regarded as garden-variety swearing was then regarded as career-ending obscenity. In Britain today, as across much of the Western world, these conservative boundaries have dissolved with the culture that birthed them, but expression is not free. They have simply been replaced by a new form of linguistic correctness, maintained by a new elite, which is now not traditionalist or conservative but leftist and liberal.

Today there exists an unofficial political and cultural line, a heavily-policed linguistic orthodoxy which all of us know we cannot challenge without a penalty. The punishments for crossing this line—for expressing an unorthodox opinion, using incorrect vocabulary, or challenging those who police the orthodoxy—can range from public abuse on social media all the way to losing jobs, livelihoods, and reputations. The chances are that if you pop over to your Twitter feed right now, you will see somebody getting this treatment.

These are the swamps into which our linguistic weapons have sunk us. Language is used dishonestly across shifting political and cultural spectrums to disguise intentions and to make excuses for tyranny of both mind and body. What ought to be our most glorious tool—symbolic thought, abstracted and represented in words—has become a crude weapon of warfare. Why?

Language is both our most effective tool and our most powerful weapon.

I am a writer, but it has taken me a long time to circle around, in my life and work, to this question. What is language? What is written language, especially? For it is writing that defines our use of language in the modern age. We see writing and reading—“literacy,” as we call it—as one of the basic necessities of life. Few people throughout history have been able to read or write, but across the world now, literacy is promoted as an unquestionable good. We measure its progress obsessively and work to extend its reach.

But the ability to read and write is also the ability to abstract. You are running your eyes right now across some marks on a screen. Why? Because they convey meaning, and that meaning is conveyed through a shared agreement about abstraction. You and I agree on what meaning a conceptual term like “abstraction,” or indeed, “conceptual,” conveys. I use a word, these marks convey that word to you, and you hopefully understand me. It should be clear already how much scope for confusion this causes. How do I know that my “abstraction” is the same as yours? I don’t. I can only do what I have trained myself to do over my long years as a writer: use these symbols in the best combination I can and hope for the best. In doing so, I struggle to convey the depth and meaning of my real, embodied human experience in terms which, at best, are weirdly abstracted from actual life.

Most humans throughout history would barely have understood the purpose of staring immobile at some marks on paper or glowing screen. The notion that they could help anyone to understand the complexity of lived reality would have seemed absurd; as it still does to many. Sometimes writers can forget how pointless, or just baffling, writing for a living seems to many people. We can forget how much we deal in abstraction. We can confuse these words for the reality they are intended to convey. This confusion—of the signifier and the signified, the original reality and its distilled essence—is one of the reasons we end up with language wars. We think, at some level, that if we can control the signifier, then that control will bleed out into reality. We think that using our symbols to define reality will change the nature of reality itself.

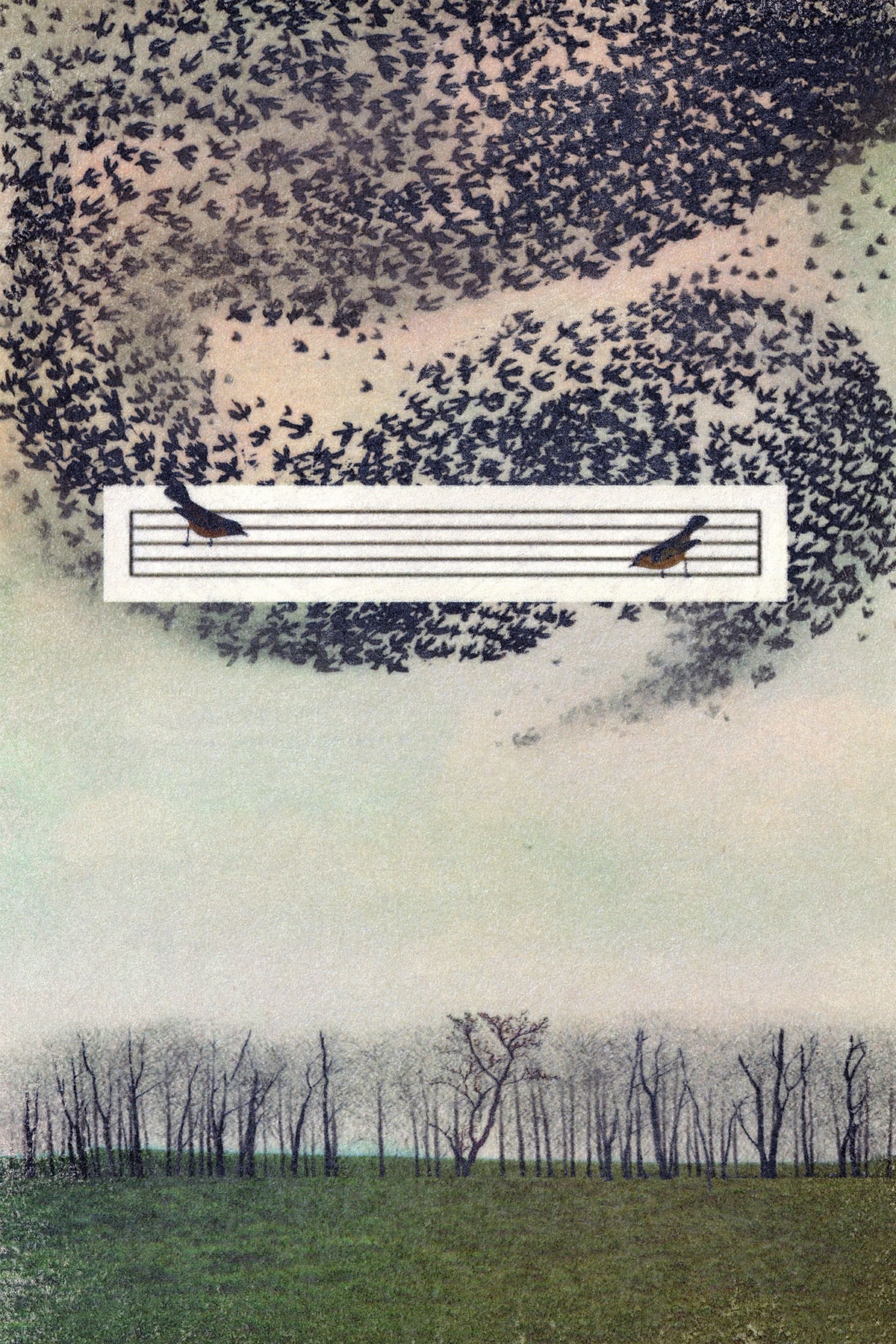

Words are not real. I think we have forgotten this. In a culture that increasingly deals with abstracts, it is a dangerous form of forgetting.

The cultural ecologist David Abram, in his book The Spell of the Sensuous, claims to have identified the moment when written language jumped the boundary from rootedness to abstraction. The building blocks of Semitic written language—the aleph-beth—he explains, were a series of characters each based on a consonant in spoken language. There were twenty-two of them, and with their advent “a new distance opens between human culture and the rest of nature.” Why? Because, unlike every written language before it (Egyptian hieroglyphics perhaps being the best-known example), the aleph-beth—which later became, via the Greeks, our own alphabet—was made up of written characters which no longer directly represented an actual thing out in the real world.

The original letter A, writes Abram, may once have represented the shape of an ox’s head; O may have been an eye; Q the back end and tail of a monkey. But once the Semites got hold of them, turned them into abstract symbols, and wrote them down—with the Greeks later finishing the job—the link between culture and nature was finally lost. Written language was no longer visually tied to the world of physical, real, naturally-occurring things. Letters were now only marks, signifying nothing but their own internal meaning. Humans could speak to other humans in a code understood by, and inspired by, only themselves. Language had become internalized. It no longer represented the forms of the world around them. It represented only what they saw in their minds.

The question then became: what kind of minds?

In his 2009 book The Master and his Emissary, writer and former psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist posits, in exhaustive and often fascinating detail, the notion of what he calls “the divided brain.” Drawing on neuroscience, history, and philosophy, he suggests that the two hemispheres of the human brain have different functional approaches to perceiving reality. While popular mythology might perceive the “right brain” as dealing with “emotion” and “left brain” with “reason,” McGilchrist suggests the division is more fundamental. The brain’s right hemisphere, he suggests, understands the whole picture; the left hemisphere understands how to examine its parts. Both are useful—necessary, in fact—to human life; but a sane way of relating to the world outside our heads requires the left hemisphere to be a servant of the right. In other words, the ability to pick life apart is only useful if it is in service to a more holistic understanding.

Modernity, suggests McGilchrist, has been the process of the “Emissary”—the left hemisphere—usurping the “Master”—the right. Now we are paying the price.

This, if true, explains rather a lot. It explains why we believe “reason” to be the supreme human achievement, and the basis for our society, when it is more likely that reason evolved as a tool for serving our intuition. It explains why concepts like “intuition” are dismissed in our reason-obsessed culture, despite having a clear evolutionary basis and day-to-day utility. It explains why atheists don’t understand religion. It explains why we fail to grasp the utility of myth. It explains why we imagine the world to be a “resource” rather than an intertwined network of living things. It explains the subject-object split which has bedeviled us since the Enlightenment. It explains atom bombs and AI and ecocide.

It explains, too, why our language has become utilitarian and abstracted and often toxic: why it so often serves the purpose of those who would dismantle the world or repurpose it for human use. Language no longer serves the part of the brain which, in McGilchrist’s words, “believes but does not know.” It serves the part which “knows but does not believe.” Our words no longer serve wholeness. They serve fragmentation, and we have used them to justify the building of a fragmented world.

If you cannot solve a problem with the mindset, or the tools, which created it, what does this mean for those whose tools are words? It is the question I am coming to now and cannot avoid. Because I have a suspicion—a suspicion I have long held but have circled around, not wanting to fully face. It is this: That words are the problem. That language itself—or at least the kind of language we use, abstracted, boiled down into these ink marks—is part of the process by which we desacralize the world. That writing, especially, is a tool of ecocide.

Step outside the word-bubble—take yourself beyond the literate cultures of the post-Enlightenment world—and you soon find people who would agree. We have killed off most of the world’s oral cultures, but those which remain, which cling on, can sometimes open us out—we, the abstracted ones—to the damage we do with our writing, with our symbolic abstraction, with our constant flow of chatter, with our endless words.

In 1980, Russell Means, member of the Oglala Lakota people, of the Sioux tribe, activist in the American Indian Movement, occupier of Alcatraz and Wounded Knee, gave a speech about what he stood for, and why he, with many other American Indians—his preferred terminology—were rising up against established structures. Means had been reluctant to make a public speech and had to be persuaded to do so. He agreed only on one condition: that he didn’t have to write it down. He explained his reasoning in his address:

The only possible opening for a statement of this kind is that I detest writing. The process itself epitomizes the European concept of “legitimate” thinking; what is written has an importance that is denied the spoken. My culture, the Lakota culture, has an oral tradition, so I ordinarily reject writing. It is one of the white world’s ways of destroying the cultures of non-European peoples, the imposing of an abstraction over the spoken relationship of a people.

Any notion of “liberation,” for American Indians or anyone else, said Means, had to go way beyond battles about surface structures—way beyond arguments about economics or politics. It was not a question of Marxism versus capitalism, religion versus secularism, right versus left. These, according to Means, were just different shards of the same broken window:

Newton, for example, “revolutionized” physics and the so-called natural sciences by reducing the physical universe to a linear mathematical equation. Descartes did the same thing with culture. John Locke did it with politics, and Adam Smith did it with economics. Each one of these “thinkers” took a piece of the spirituality of human existence and converted it into a code, an abstraction … Each of these intellectual revolutions served to abstract the European mentality even further, to remove the wonderful complexity and spirituality from the universe and replace it with a logical sequence: one, two, three, Answer!

What does this abstracted code lead to? According to Means, this “European mind”—what McGilchrist would call the left hemisphere, or the mutinous Emissary—leads to the dis-enchantment of the world; to its reduction down into parts which can be utilized for a narrow, poisonous version of human “progress” which can only end up destroying the human spirit and the web of life itself:

The European materialist tradition of despiritualizing the universe is very similar to the mental process which goes into dehumanizing another person … In terms of the despiritualization of the universe, the mental process works so that it becomes virtuous to destroy the planet. Terms like progress and development are used as cover words here, the way victory and freedom are used to justify butchery in the dehumanization process. For example, a real-estate speculator may refer to “developing” a parcel of ground by opening a gravel quarry; development here means total, permanent destruction, with the earth itself removed. But European logic has gained a few tons of gravel with which more land can be “developed” through the construction of road beds. Ultimately, the whole universe is open—in the European view—to this sort of insanity.

Speaking as a European, I am bound to argue with Means about the geographical descriptor of this kind of mentality. While it may have originated in Europe, it is something deeper, something not moored in place or race, which is why it has spread so fast to all continents and cultures over the last half century. It is the triumph of the Emissary, freed from his chains by our unmoored words.

What languages does the Machine not speak?

How can the servant be put back into his place again, if he ever can? Primitivist philosopher John Zerzan’s ongoing explorations of the source of humanity’s “alienation” from the rest of life led him at one point to the same question which began this essay. His conclusion was as radical as it comes:

In much the same sense that objectified time has been held to be essential to consciousness—Hegel called it “the necessary alienation”—so has language, and equally falsely. Language may be properly considered the fundamental ideology, perhaps as deep a separation from the natural world as self-existent time. And if timelessness resolves the split between spontaneity and consciousness, languagelessness may be equally necessary.

Two things detach us fatally from the rest of nature, says Zerzan here. Firstly, our conception of time—of the past and the future, which prevents us from simply existing in the moment. And secondly, language. If this is true—and it sounds convincing to me—what is to be done?

What is to be done? As I type that question, as the symbols which represent its meaning appear on the screen before me, I can’t help smiling. It is the kind of question which only the Emissary would ask. It is a left hemisphere question, a subject-object question. “One two three, Answer!” as Russell Means put it. And the answer to this non-question is, of course: nothing. There is nothing to be “done” about who and what we are, at least if that means identifying a problem and then fixing it. The notion of identifying “problems”—of using language as a tool to pin things down, define them, dissect them, and then improve upon them—is fatally flawed. Life is not a problem to be solved. It is a state to be dwelt in. To believe anything else is to walk the path toward tyranny; the path we have long been walking, even as we believe we are on a pilgrimage toward liberation.

No, there is no “solution” to the “problem” of language, any more than there is a “solution” to the “problem” of being human. But there are other languages, and other ways of using them. Standardized globalized English, written down and spread throughout the networks, will always serve its Master, the Machine monoculture that is killing Earth. Form defines function. The Machine speaks through our words. Global capitalism has squatted on my native tongue, English, and transformed it into the language of its attendant globalized “culture,” which is not really a culture at all but the product of a world-spanning economic machine intent on erasing all boundaries, borders, and particularities in the name of Earth-eating growth.

This leaves me, an English man, writing in English, with a question. If this language—and not only this language—has become a tool of control, what kind of language could be a tool to undo it?

Another way of framing that question: what languages does the Machine not speak?

If the Emissary runs our world, then we all speak his language, because we have all been trained to. It is the language of clarity, dissection, parts and not sums, specialization, dis-enchantment, reason, theoretical rather than practical expertise, technological “solutions,” bureaucracy, abstraction, mechanism. The Emissary will, left unchecked, turn our world into a machine, because he thinks it already is one. In the process, he will turn us into machines too.

Linguistically, then, we should all be encouraging the Master to regain power. This means working with the ways of seeing and communicating which Machine culture downplays or ridicules, but which every traditional society before modernity’s advent understood and worked with. That means myth, religion, practical expertise founded upon physical work, rooted imagery, holistic conceptions of life, communication with non-human beings, poetry, complexity, questions that do not have answers, questions which are not questions at all. It means seeing time as a circle, not a line, life as a process, not a puzzle to be solved, death as a part of that life, not an enemy to be defeated. Sometimes—horror of horrors—it means embracing unknowing. It means learning to stop and be silent.

It means, in short, upending Machine society’s ways of conceptualizing the world we are part of. Impossible? Well, of course, if you are “thinking globally,” as we are all instructed to. This is no political solution. But then, this is not a political project. It is not work for a bureaucracy, a state, a “movement.” Think like that, use those words, and you have fallen right back into the pit you just crawled up from.

No, this is small, intimate, personal work. It is the work of a life, or several lives. Until you know how to speak, you will have nothing useful to say. Until you understand what kind of weapon your language was designed to be, you will never learn what war the Machine has sent you out to fight, and how you might flee the battlefield for the mountains.

On our long journey into the age of ecocide, we forgot how to speak, or even what we should be saying. We certainly forgot how to listen, and what to listen to. Silence beckons, now. Attention must be paid. The Master must be returned from his long exile. Come. Begin.